DON'T BE ASHAMED OF YOUR OWN STUPIDITY

- Tobias Meinecke

- Feb 9, 2020

- 5 min read

Updated: Feb 10, 2020

DOUBLE ACADEMY AWARD WINNING DIRECTOR MILOS FORMAN ON THE PROCESS OF COLLABORATION IN THE WRITER'S ROOM

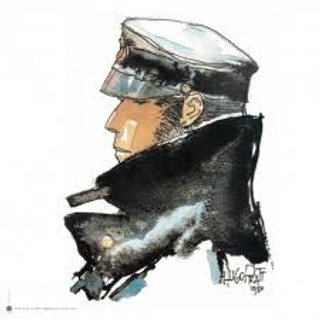

MILOS FORMAN (1931-2018)

"I impose only a few rules on writing collaborations. One is that you can’t waste time talking generalities. Another is that you can’t feel ashamed of your own stupidity. You need to feel the freedom to blurt out any dumb idea that pops into your mind—it often takes ten inane ideas to come up with a good one. Still another rule: if you have a new idea, you’ve got to show precisely how it ties into the existing script and how it then builds step by step. My last rule is that all the writers involved in a screenplay must sign off on the final version. We work until we have a script that everyone can put his name on, which can sometimes get to be as bruising as a tough jury deliberation."

If you ask me, the late DOUBLE ACADEMY AWARD winning director Milos Forman (1932 - 2018) counts as one of the true masters of the art, who should be on anyone's ALL TIME TOP100 DIRECTORS list. Name me those with a greater body of work than his. You won't find too many.

Full disclosure - I'm biased. I was Milos' student in the 1990s. Unbeknown to many, Forman was not only a great filmmaker but also a master teacher. For 40 years, while on an illustrious and curious career path that took off with the success of LOVES OF A BLOND in Chechoslovakia in the early 1960s and let to the Academy Award recognized heights of AMADEUS and ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO'S NEST, and includes many more masterpieces (FIREMEN'S BALL, THE PEOPLE VS LARRY FLYNT a.o.) , Forman taught a masterclass in directing at Columbia University in New York.

During my research for a documentary project on Milos Forman teaching film some of the lessons he hammered into us students came back to me as vividly as if I heard them yesterday. One them is the above lesson to "not be ashamed of your own stupidity" when working on a script in the writer's room - a reminder that creativity is playful, is trusting, is relentless.

This is what he had to say about collaborating in the writer's room, quoted here from his memoir TURNAROUND. He is referring to the work on the movie version of HAIR.

MILOS FORMAN ON COLLABORATION

Persky helped me with putting together a list of young writers, most of whom had probably been shaped by the sixties. I called every name on the list, asking my candidates if they’d be interested in working on Hair. Mostly they were, so I told them to listen to the recording before we got together. They all said they’d give it a listen and some thought, but I should have known better than to believe them. I’m not sure if the writers I saw simply didn’t give a damn or if they were afraid of having their ideas stolen, but all I got from them was a lot of dense theories about the expanding universal consciousness, the immorality of war, the morality of protest, and so on. I could hardly follow their abstractions, and I was starting to lose faith.

One afternoon, a short, dark, and intelligent-looking young man named Michael Weller came to interview with me. He was a playwright who had already penned Moonchildren, a very successful play, and who had been recommended to Persky by Peter Shaffer. “So,” I asked him, “did you have a chance to think about how to do Hair?” “Yes,” he replied. “And?” “Mr. Forman, I don’t have a fucking clue,” he said, looking me straight in the eye. “I don’t have a fucking clue either,” I said with an immense sense of relief. “Call me Milos.”

Michael was a wonderful collaborator who ended up writing both Hair and Ragtime for me. I don’t look for a screenwriter who merely executes my ideas. I often don’t know what I want until I have it, so I need a strong personality who can engage me in creative dialogue.

Michael has always had his own sensibility, and he didn’t mind going toe to toe with me. Our most difficult task came right at the beginning: we had to find a natural way to introduce the first musical number. I love old musicals where hard reality suddenly goes opera, where the music swells and strangers riding on a bus inhale deeply and break into three-part harmony, but I accept that freedom as a part of the old charm of the genre. I didn’t want any operas erupting in Hair, so I thought that the first transition from words to music was what mattered most: if we could slip the first song into the story organically, we’d set the tone for the whole film and be free to weave in the other songs as we saw fit.

The solution that Michael and I came up with has the draftee Claude at the beginning of his journey to Vietnam. He says good-bye to his father on a road that cuts through the farmlands of Oklahoma and gets on a bus that will take him to New York City. He has a window seat, and, squinting into the blinding sun, staring at the roadside, he rides it straight into the draft-card-burning, hallucinatory Age of Aquarius.

Some of the best ideas that Michael and I came up with grew out of fierce arguments. For example, for a long time we couldn’t find an ending. In my memories now, it feels as if it took weeks, but perhaps it was only a few days. We had taken the story of the Oklahoma draftee, played by John Savage, through his culture shock in New York, his friendship with the band of hippies led by Treat Williams, his LSD initiation, and his separation from his new friends when he decides to report to the army after all. We had his character in the boot camp in Arizona and we had his New York friends on the way there to try, for one last time, to save him from the army and from Vietnam, when we stalled. We wrote several scenes, but none of them gave the proper sense of closure to the screenplay. Michael had his idea for the ending, which I didn’t like, and I had mine, which he didn’t like, and as we argued about the two notions, our respective positions hardened.

I impose only a few rules on writing collaborations. One is that you can’t waste time talking generalities. Another is that you can’t feel ashamed of your own stupidity. You need to feel the freedom to blurt out any dumb idea that pops into your mind—it often takes ten inane ideas to come up with a good one. Still another rule: if you have a new idea, you’ve got to show precisely how it ties into the existing script and how it then builds step by step. My last rule is that all the writers involved in a screenplay must sign off on the final version. We work until we have a script that everyone can put his name on, which can sometimes get to be as bruising as a tough jury deliberation.

During our search for an ending, Michael and I were hopelessly locked. We kept talking at each other, agreeing on less and less, getting more and more sarcastic, raising our voices. I’d never gone through such a battle of wills. There didn’t seem to be any way out of the stalemate when suddenly, somehow, during another stream of stupidities, we got the idea that enabled us to get the rest of the screenplay down on paper in half an hour: what if the hippie leader Berger and his troop arrive at the army base just as it’s going on an alert and being closed off? Then Berger would have to sneak into the barracks and switch places with the Oklahoma draftee in order to spring him from the base so that his old buddy can, for one last time, make love to Sheila.

While the New York flower child plays soldier on the base, the whole unit is suddenly ordered to pack up and move out, destination: body-bag Vietnam.

Comments